|

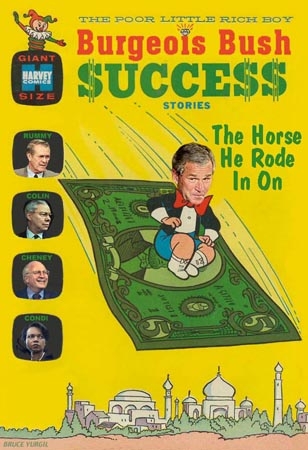

BUSH BASHING |

|

BUSH SLACK ON CORPORATE CRIME--especially his family's

Business In The Beltway WASHINGTON, D.C. - Two years after President George W. Bush established by executive order the Corporate Fraud Task Force to, as he put it, "use the full weight

of the law to expose and root out corruption," the Federal Bureau of Investigation is launching fewer white-collar inquiries than before Sept. 11, 2001. A new Government

Accountability Office report examining the effects of the FBI's shift to counter-terrorism finds it began 32% fewer new white-collar

investigations in fiscal 2003 than in fiscal 2001. (The report does not count new whistleblower cases in its analysis.) Influence and bailouts a business tradition in Bush familyBy ROBERT TRIGAUX © St. Petersburg Times, published October 29, 2000 Once upon a time, a rich and powerful father gathered his four young sons and urged them to become rich and powerful, too. Take risks. Push yourselves. Influence others, he ordered in a bold voice. Then he whispered, "And if you muck things up, a fairy godfather will always appear to make things better." Those may not have been the precise words spoken, but this is no tall tale. It's the business model adopted long ago by George and Barbara Bush to propel sons George W., Jeb, Marvin and Neil into the high ranks of industry and, at least for two boys, politics. Sure, by now in the presidential campaign Dubya's dubious business transactions have been poked at repeatedly by the media. No question, Jeb's numerous and often questionable business dealings have been scoured more than once. Little has been written about Marvin, an investment adviser. Neil, the youngest, took some serious legal heat in the 1980s for his role in the demise of a Denver savings and loan. But he has since retreated to the Bush home turf of Houston and largely disappeared from the national spotlight. Altogether, the Bush boys' business deals have received scant attention. What's intriguing is that, time and again, all four brothers have chosen to use a remarkably similar two-step business model. STEP 1: Leverage the Bush family name and a small personal investment into really big money, always provided by others. STEP 2: If any deal goes sour, exit early with personal fortune intact. Or rely on a bailout from one of Dad's fairy godfathers: some of the thousands of wealthy Republican fundraisers and longtime supporters of former President Bush. Of course, playing off the privileged and famous Bush name is inevitable. But to the Bush boys, dubbed the "Shrubs" by detractors, it's become a chronic dependency. A habit of striking consistency. The Bushes uniformly deny any wrongdoing and insist they haven't profited improperly on their family's political and financial connections. But let's just take a quick peek at some of the more interesting "Bush business model" deals pursued over the years by each of the boys. George W.Alaska construction: At age 27 and halfway through two years at Harvard Business School, Dubya spent the summer of 1974 in Alaska working for a small airline-and-construction business. The company, Alaska International Industries, had received a letter from an executive at a Houston construction company asking about a job for Bush. The aviation arm of Alaska International had an unusual list of clients that just happened to include the shah of Iran and the Central Intelligence Agency. Dubya's father would be appointed CIA director the following year. Oil deals: In Texas, Dubya took his $50,000 trust fund and in 1977 started his first company, Arbusto Energy Inc. He got friends to invest in various drilling ventures that mostly went nowhere (but did generate big tax deductions). Friendly investors arranged a 1984 deal in which struggling Arbusto was acquired by another drilling company called Spectrum 7. When Harken Energy bought Spectrum in 1986, George wound up on the board with a $120,000 consulting gig and $530,380 worth of stock. In the midst of his father's presidency in 1990, Bush unloaded his Harken shares for $848,560. Less than two months later, Iraqi troops marched into Kuwait, throwing the oil business into turmoil. Harken shares plummeted and the company reported a $20-million quarterly loss. The Securities and Exchange Commission investigated Dubya for improper insider trading but issued no reprimand. At the time, the SEC was headed by Richard Breeden, a former aide to President Bush. Baseball: Dubya was appointed managing partner of the Texas Rangers baseball team, even though he put up only $600,000 of mostly borrowed money for a 1.8 percent stake in the team. Among the big backers buying the Rangers were William DeWitt (a fellow Yale alum of Dubya's) and Mercer Reynolds. Both were major contributors to President Bush's campaign. Earlier, the two also were in on the rescue of Dubya's oil company. Dubya later sold out of the Rangers' ownership group. His take: $15-million. That sum made Dubya rich and finally in a comfortable position to pursue a political career. In 1998, Dubya and his wife reported income of $18,405,524, on which they paid federal taxes of $3,772,252, or 20.5 percent. Most of their 1998 income came from long-term capital gains. And nearly all of that resulted from the original $600,000 investment in the Texas Rangers. JebMiami real estate: After relocating to Miami from Texas, Jeb quickly teamed up with Cuban-American real estate investor Armando Codina. A prominent fundraiser and staunch supporter of President Bush, Codina took Jeb under his wing and eventually made him a partner in the Codina Bush commercial real estate business. Jeb, with no investment, would get 40 percent of the real estate company's profits plus chances to invest in other ventures. After Jeb entered the race for Florida governor and lost to Lawton Chiles in 1994, Codina welcomed Bush back to the firm. That relationship made Jeb a millionaire, with a net worth of about $2.4-million by 1997. Water pumps: In 1988, the same year Jeb's father became president, Jeb formed a partnership with David Eller, Broward County's Republican fundraiser, to market irrigation and flood control pumps overseas. Bush went to Nigeria, where he pledged his father would increase aid to developing countries, according to Nigerian press reports. Nigeria received $74-million in loans from the federally backed Export-Import Bank of the United States to buy the pumps, giving Jeb a healthy commission. Twelve years later, Nigeria has yet to repay most of the loans. Golf community, IBM property: When Bush and Codina needed to unload Deering Bay, an upscale South Florida golf community that had lost millions, they found a buyer in Florida developer and major Republican fundraiser Al Hoffman. Hoffman would become the primary finance chairman of Jeb's successful campaign for governor. Separately, in what Jeb considers one of his biggest deals as a real estate broker, his firm was hired by IBM Corp. to find a buyer for its massive Boca Raton office park. Jeb handled the sale personally. He eventually sold the property for about $46-million in 1997 to a group that included Mark Guzzetta, a key fundraiser for then-former President Bush. Guzzetta later co-chaired Jeb's campaign for governor. Jeb said he got a great sales price for IBM. This year, Guzzetta and his partners sold the property for about $140-million, nearly three times what they paid a few years ago. MarvinCoral Gables director: As an executive of Winston Partners Group, a northern Virginia investment company, Marvin was named to the board of South Florida-based Fresh Del Monte Produce in 1998. The international fruit and vegetable company, run by the Abu-Ghazaleh family, has a board full of Bush family friends. Among them: Stephen Way, who heads Houston-based HCC Insurance Holdings and is a major fundraiser for Bush family politicians. Way also invited Marvin on to the HCC board last year, a position that pays Bush thousands of dollars and gave him options to purchase 12,500 shares of HCC common stock. Stratasec: Marvin was recruited to join the board of this secretive Virginia security company that serves international corporations and governments. The company is awash in ex-government security and military personnel. Among them: Barry McDaniel, who served during the Reagan years as deputy director of readiness for the U.S. Army Materiel Command; and retired U.S. Air Force General James A. Abrahamson, who served as director of President Reagan's "Star Wars" Strategic Defense Initiative. The company touts such major customers as Dulles airport near Washington, as well as Los Alamos National Laboratories (where former scientist Wen Ho Lee pleaded guilty to improperly downloading nuclear weapons design secrets). KuwAm Corp.: The investment company, with roots in Kuwait (the country "liberated" by President Bush's Gulf War), is a large backer of Stratasec. Stratasec chief executive Wirt Walker also is a managing director of KuwAm. And KuwAm chairman Mishal Yousef Saud Al Sabah also sits on Stratasec's board. NeilSilverado failure: In the mid-1980s, Neil served as a director of Denver's Silverado Savings & Loan. The bank loaned more than $100-million to Neil's two partners in JNB Exploration, their unsuccessful oil company. Silverado later failed, in part because Neil's two partners did not repay $132-million in loans. After years of regulatory hand-wringing, Neil was fined $50,000 for ethical lapses. He did not appeal the fine. Oil deals: Like brother Dubya, Neil went into the oil business with poor results. In 1989, he bailed out of JNB Exploration, the company where he became president with a personal investment of a few hundred dollars. His next company, Apex Energy, was formed with a personal investment of $3,000, plus a $2.3-million loan from the federal government's SBA program. Like JNB, Apex went belly-up with few assets to repay the SBA. Afterward, Bill Daniels, a cable-TV magnate and prominent contributor to President Bush, offered Neil a job. Interlink: Neil now runs Interlink Management Corp., a Houston business based in the same building as his father's office. Interlink invests in small companies such as Pennsylvania-based Lithium Technology (rechargeable batteries) and represents Universal Display Corp. (flat panel displays) in Asia. Interlink's executives included "Bush Pioneers": fundraisers who have raised at least $100,000 for Dubya's campaign. Building a political dynasty has been a priority of George and Barb Bush for decades. Almost 40 years ago, in the height of the Kennedy era, a competitive George Bush was heard to say: "Just wait 'til I turn these Bush boys out." So far, the former president and wife have done a pretty good job. If you don't look too closely. -- Robert Trigaux can be reached at (727) 893-8405 or trigaux@sptimes.com. Another Costly Bailout? Three troubled airlines are moving toward possible default

of their pension plans, and others could follow. The worst case would throw billions of dollars in pension liabilities onto

the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corp., a U.S. government agency that insures private retirement accounts for 44 million people.

It pays benefits of failed plans, but within certain limits. The agency is already running a $10 billion deficit. It has sufficient

assets to meet near-term obligations, but a massive airline pension default could throw it into bankruptcy and trigger a huge

taxpayer bailout. Tuesday, August 24, 2004 Scratch-offs are for losers. Junk bonds, energy futures, insider sell-offs and golden parachutes are for winners. So don't let us ever catch you in the act — scratching, that is. A

few weeks ago a Waco couple found out that the government was to strike down upon them with great vengeance. A former Waco

convenience store manager and her husband were indicted for scratching off a sneaky peak at the validation code of lottery

tickets for sale. Prosecutors say the two then ran the numbers on the computer to see if they were winners, and bought the

winners. Prosecutors say surveillance cameras caught it on video. It's only speculation how much lottery money store manager Shawnda Shoemaker and husband Johnny

Ray might have pocketed. One can only speculate what the penalty would be for the second-degree felony: influencing the selection

of a lottery winner. The fact that the crime carries a maximum 20 years in prison caused one Waco man to vent some steam. He called to complain about how the law treats "peons" compared to "members of the

monarchy." It's possible the Shoemakers may never see prison, which would negate

his point. But he wasn't calling on the phone to support them. He was wondering why this couple was facing a possible 20 years

while Andrew Fastow, the former CFO of Enron, who ruined countless lives and squandered billions, agreed to half that. The caller was wondering why so many big shots always seem to float off without their suits being

wrinkled while the little guys who run afoul for lesser offenses end up in the belly of the beast. After corporate scandals looked to become the trademark of the Bush economy, federal officials made a habit

to feature corporate crooks in handcuffs doing the "perp walk." That would send a message, they said. At the same time, Americans watched Bush's friend, Enron chairman "Kenny Boy" Lay, walk the manor, maybe

a little sweaty-lipped, but for months no worse for wear. How long did it take to bring Lay before a judge on criminal charges?

Essentially the length of one presidential term. Now he faces the prospect of 175 years in prison and fines of $5.75 million.

But we'll see if his punishment exceeds that of lottery-ticket tampering. Back in the 1980s a lot of Americans lost their life savings when corrupt individuals put savings

and loans at risk. One of the biggest offenders was Republican national committeeman Charles Keating. Under his fiduciary

watch at Lincoln Federal Savings, 21,000 mostly elderly investors lost all they had. Taxpayers had to swallow $3 billion of

Lincoln's losses. Keating served four years in prison. At the same time the board

of Silverado Savings & Loan in Denver oversaw the frittering away of $1.6 billion in other people's money. Presidential

son/brother Neil Bush, a member of the board of directors, profited greatly from a free-wheeling buddy system there. So did

other Silverado wheeler dealers. Bush's penalty after it all shook down was a $50,000 fine. His legal fees were put up by

a donor. It's a good thing for Neil he didn't get his hands on a roll of scratch-offs.

I'd say the syndrome is summed up by a posting about the S&L scandal on motherjones.com: "If you steal, steal big." |

|

it takes a special type of slime to be a leading a Republican

or a Democrat

Politican is another dirty word!

Politican is another dirty word! |