|

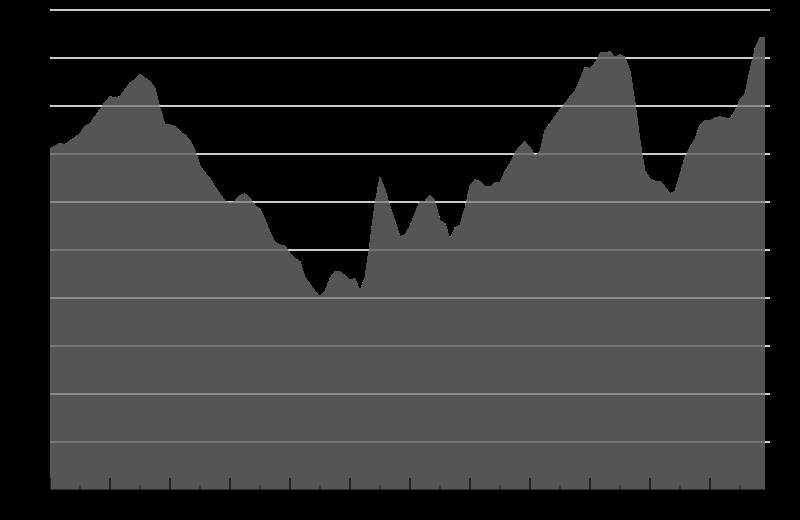

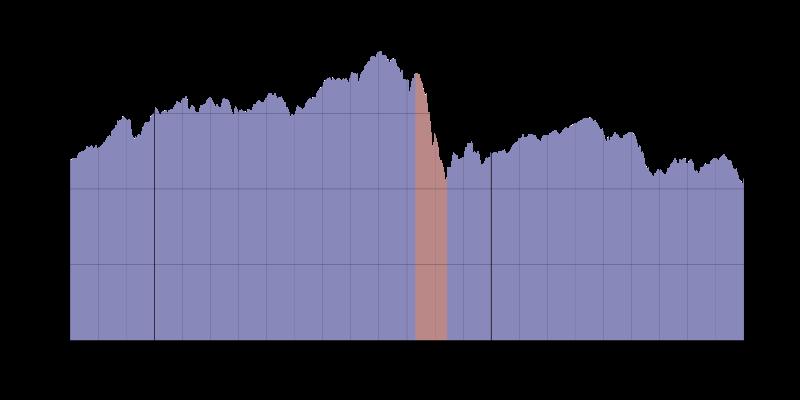

CRASH 2008-09 -- first wave |

|

Three Crashes--Models

Industrial production

is an excellent indicator for the economy. The 1929 Crisis Slow start: The Great Depression was not a sudden total collapse. The stock market turned upward in early

1930, returning to early 1929 levels by April, though still almost 30 percent below the peak of September 1929. Together,

government and business actually spent more in the first half of 1930 than in the corresponding period of the previous year.

But consumers, many of whom had suffered severe losses in the stock market the previous year, cut back their expenditures

by ten percent, A severe drought ravaged the agricultural heartland of the USA beginning in the northern summer of 1930. Over expansion of manufacturing in the 1920s entail further contraction. In early 1930, credit was ample and available at low rates, but people were reluctant to add new debt by

borrowing. By May 1930, auto sales had declined to below the levels of 1928. Prices in general began to decline, but wages

held steady in 1930. Conditions were worst in farming areas, where commodity

prices plunged, and in mining and logging areas, where unemployment was high and there were few other jobs. In September of 1929 the market lost 17%. This made investors, most of whom were levereged,

nervious. For example if they were leverged 100%, then they had lost twice the 17% down turn. The market made

a modest recovery, then on Monday October 28 it dropped 13%. On the 29th if fell another 12%. The market lost

in 2 days $30 billion, which is more than the cost of World War I. In the 1920s the Amercian consumer and businesses relied upon cheap credit. The economic down turn and stock market drop of 1929 resulted in defaults. This resulted in an snow-ball effect bring about massive layoffs and wage reductions which produced more

defaults. The run on the stock market was a result of weakening economic conditions

and inflated stock prices. In the first year since the market fall of October 1929 there were 733 bank failures,

but by 1939 over 9,000 failed, and with them deposits vanished. The run

on banks began in early 1933. By the end of 1933 depositors had lost $140 billion. Tight credit and poor prospects for

recovery slowed the rate of recovery from the depression's bottom of 1933. Unemployment

hit 25% that year. In 1937 the American economy took an unexpected nosedive,

lasting through most of 1938. Production declined sharply, as did profits and employment. Unemployment jumped from 14.3% in

1937 to 19.0% in 1938.

Savings and Loan Crisis, 1980s The savings

and loan crisis of the 1980s and 1990s (commonly referred to as the S&L crisis) was the failure

of 747 savings and loan associations (S&Ls) in the United States. The ultimate cost of the crisis is estimated to have totaled

around USD$160.1 billion, about $124.6 billion of which was directly paid for by the U.S. government—that is, the U.S.

taxpayer, either directly or through charges on their savings and loan accounts[1]—which contributed to the large budget deficits of the early 1990s. The deficits were subsequently eliminated

during the Clinton Administration. The concomitant slowdown

in the finance industry and the real estate market may have been a contributing cause of the 1990–1991 economic recession. Between 1986 and 1991, the number of new homes constructed per year dropped

from 1.8 million to 1 million, the lowest rate since World War II. HOW HISTORY REPEATS ITSELF: The damage to S&L operations led Congress to act, passing a bill in September 1981[5] allowing S&Ls to sell their mortgage loans and use the cash generated to seek better

returns; the losses created by the sales were to be amortized over the life of the loan, and any losses could also be offset

against taxes paid over the preceding 10 years. This all made S&Ls eager to sell their loans. The buyers – major

Wall Street firms – were quick to take advantage of the S&Ls' lack of expertise, buying at 60%-90% of value and

then transforming the loans by bundling them as, effectively, government-backed bonds (by virtue of Ginnie Mae, Freddie Mac, or Fannie Mae guarantees). A large number of S&L

customers' defaults and bankruptcies ensued, and the S&Ls that had overextended themselves were forced into

insolvency proceedings themselves. The U.S. government agency FSLIC, which at the time insured S&L accounts in the same way the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation insures commercial bank accounts, then had to repay all the depositors

whose money was lost. From 1986 to 1989, FSLIC closed or otherwise resolved 296 institutions with total assets of $125 billion.

An even more traumatic period followed, with the creation of the Resolution Trust Corporation in 1989 and that agency’s resolution by mid-1995 of an additional

747 thrifts. A Federal Reserve Bank panel stated the resulting taxpayer bailout

ended up being even larger than it would have been because moral hazard and adverse selection incentives that compounded the system’s losses. While not part

of the savings and loan crisis, many other banks failed. Between 1980 and 1994 more than 1,600 banks insured by the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) were closed or received FDIC financial assistance.

From 1986 to 1995, the number of US federally insured savings and loans in the United States declined from 3,234 to

1,645. The market share of S&Ls for single family mortgage loans went from

53% in 1975 to 30% in 1990. U.S. General Accounting Office estimated cost of

the crisis to around USD $160.1 billion, about $124.6 billion of which was directly paid for by the U.S. government from 1986

to 1996.[1] That figure does not include thrift insurance funds used before 1986 or after 1996. It also does not include state

run thrift insurance funds or state bailouts. The concomitant slowdown in the

finance industry and the real estate market may have been a contributing cause of the 1990–1991 economic recession.

Between 1986 and 1991, the number of new homes constructed dropped from 1.8 to 1 million, the lowest rate since World War

II. |

||||

|

The putative fix of October

2008 What’s

happening? (1) Proposed deal’s modifications are just window dressing that will be ignored once Paulson gets

the authority to dole out the funds. Thus the Democrats and Republicans appear

to have satisfied critics without substantially changing the original bill. (2) The demand for immediate

passage was just a sales ploy and that even if passed the feds were planning to wait at least two weeks before there was any

substantial disbursement of funds. (3) Existing executive pay packages are not to be undone. (4) To add FDIC regulatory authority to review banking industry’s determination of assets, and permit

the issuing of short-term loans (5) Progressives want aid

to homeowners in default (6) Republicans

and some Democrats want in exchange for their support a provision which will further reduce the corporate tax rate. If they

weren’t in bed with the very industries they are regulating, a New

Deal type of approach would be adopted. Such a deal would be similar to the proposal

of Rep. Donna Edwards (D-Md.) “It’s a clean slate and its our job for our constituents and for the country for us to say there’s

another way.” That means throwing out Paulson’s plan, going back to the drawing board, and constructing a plan

that creates a Reconstruction Finance Corporation-type agency to buy some bad loans; nationalizes and restructures failing

banks; invests heavily in job-creating infrastructure programs; provides direct aid to homeowners; includes new regulations

for Wall Street (i.e., banning short-selling shenanigans, reinstating and updating the Glass-Steagall Act, etc.); reforms

bankruptcy laws to help homeowners renegotiate their loans; expands the FDIC’s scope and authority; and pays for any

taxpayer losses with a tax on the financial industry. Short of this, we should support the effort by House progressives to

use the No BAILOUT Act to forge a Left-Right congressional coalition around a bill that at least strengthens the FDIC and

protects taxpayers.” Don’t miss the collection of Pod Cast links Nothing

I have seen is better at explaining in a balanced way the development of the national-banking system (Federal Reserve, Bank

of England and others). Its quality research and pictures used to support its

concise explanation set a standard for documentaries--at http://www.freedocumentaries.org/film.php?id=214. The 2nd greatest item in the

|