|

ECONOMICS |

|

Greenspan & Federal Reserve's warning about debt

Things have deteriorated since then. Things have gotten worse, the hole the neocons has dug is much deeper. The economic stats are worse than bad: the trend is toward

greater disparity of wealth and on top of that the Fed Eyes Asset-price Rises Closely: Greenspan Jackson Hole,

Wyo (Ruters), Federal reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said on Friday (8/26/5) the U.S. central bank was paying increasing

attention to asset price rises since these were having a growing impact on world economic activity. He warned also that buying

power fueled by higher prices for such assets as stocks and homes could disappear if investors turn cautious.

In remarks prepared for delivery to the annual central bank

symposium sponsored by the Kansas City Federal Reserve, the Fed chief said the vast increase in market value of assets stemmed

partly from faith that economic risks were low. "Such an increase in market value

is too often viewed by market participants as structural and permanent," said Greenspan, who is due to step down as the U.S.

central bank's chairman at the end of January. "To some extent, those higher values may be reflecting the increased flexibility

and resilience of our economy." But he added that "newly abundant liquidity can readily disappear" if investors grow wary for

some reason and demand a higher risk premium for lending. Greenspan said the Fed had to focus on such issues since

global economic activity was being influenced by capital gains on various types of assets and on the debt that sustains them. "Our forecasts and hence policy are becoming increasingly

driven by asset price changes," the Fed chief said. Economists said his remarks indicated the Fed will press

on with its steady-as-she-goes rate rise campaign. "From his comments, it is

clear that the Fed will keep raising rates, hoping to bring the housing market to a very soft landing," said Drew Matus, an

economist at Lehman Brothers in New York. Greenspan said increased investor caution, by elevating

the premiums investors demand in compensation for risk, could lead to a swift reversal in asset values if it forced the liquidation

of debts that support them. "This is the reason that history has not dealt kindly

with the aftermath of protracted periods of low risk premiums," he said. In wide-ranging remarks that touched on the changes

in policy-making over his 18-year tenure, the Fed chairman said the U.S. central bank has moved toward a risk-management approach

as globalization has become more important. Forecasts of change in the global

economic structure -- for that is what we are now required to construct -- can usefully be described only in probabilistic

terms," he said. "In other words, point forecasts need to be supplemented by a clear understanding of the nature and magnitude

of the risks that surround them." If flexibility could be maintained, he said,

"some of America's economic imbalances, most notably the large current account deficit and the housing boom, can be rectified

by adjustments in prices, interest rates and exchange rates rather than through more-wrenching changes in output, incomes

and employment." He said the growing stability of the world economy over the

past decade seemed to be encouraging investors to accept less compensation for the risks they take. "Whether the currently elevated level of the wealth-to-income ratio will

be sustained in the longer run remains to be seen," he said.

Greenspan said trade protectionism and a failure of the U.S. government to come to grips with fiscal problems were

a concern. "The developing protectionism regarding trade and our reluctance to

place fiscal policy on a more sustainable path are threatening what may well be our most valued policy asset: the increased

flexibility of our economy," he said. Article

below from Federal Reserve Board of San Francisco, Number 2005-17,July 29, 2005 FRBSF What Greenspan

is worried about, read and worry--jk What If Foreign Governments Diversified Their Reserves? |

|

World financial markets paid close attention when officials from both South Korea and Japan said that their

governments were considering diversifying their holdings of foreign reserves (Dougherty 2005 and Koizumi 2005). Many analysts

thought these announcements were partly in response to the past depreciation of the dollar; if true, then it seemed likely

that those two governments would sell some of their dollar-denominated assets, putting further downward pressure on the dollar. Since then, officials in both countries have insisted that they were not considering any major changes

to the policy of reserve holdings. Nonetheless, the potential for a sell-off of dollar-denominated assets by foreign governments

has raised some questions about the consequences of such a move. This Economic Letter attempts to put these issues

into perspective. It begins with a review of recent trends in the holdings of such assets by foreign governments and

a description of how these governments use them. Then it explores some of the risks the U.S. economy might face if foreign

governments sold off large quantities of their dollar-denominated reserves. It concludes with a discussion of some of

the costs such a sell-off would pose to foreign countries themselves. Recent trends in holdings of foreign exchange reserves and how they are used Foreign exchange reserves are holdings of foreign-denominated securities by foreign governments. One of

the major uses of foreign exchange reserves is to intervene in the foreign exchange market in order to influence the value

of the domestic currency and to serve as collateral for foreign borrowing. Suppose, for example, that a country

wants to see the value of its currency depreciate, so that the cost of its exports will be relatively lower and therefore

more attractive to foreign buyers. The government would then buy foreign-denominated securities and pay for them with domestic

currency, thus leading the domestic currency to depreciate. Governments

may also intervene in the foreign exchange market to keep the local currency stable relative to another currency in order

to reduce the risk of exchange rate fluctuations. By reducing exchange rate risk, foreign governments may promote greater

foreign trade and financial flows. A more dramatic use of foreign reserves may occur when the domestic currency is under a

speculative "attack." Reserves can be used as a "war chest" to defend the local currency and, by extension, the domestic financial

systems, in case of future runs on their currency. Following the 1997-1998 Asian financial crises, many East Asian governments

moved to accumulate large amounts of reserves to serve as collateral for their domestic financial systems and prevent future

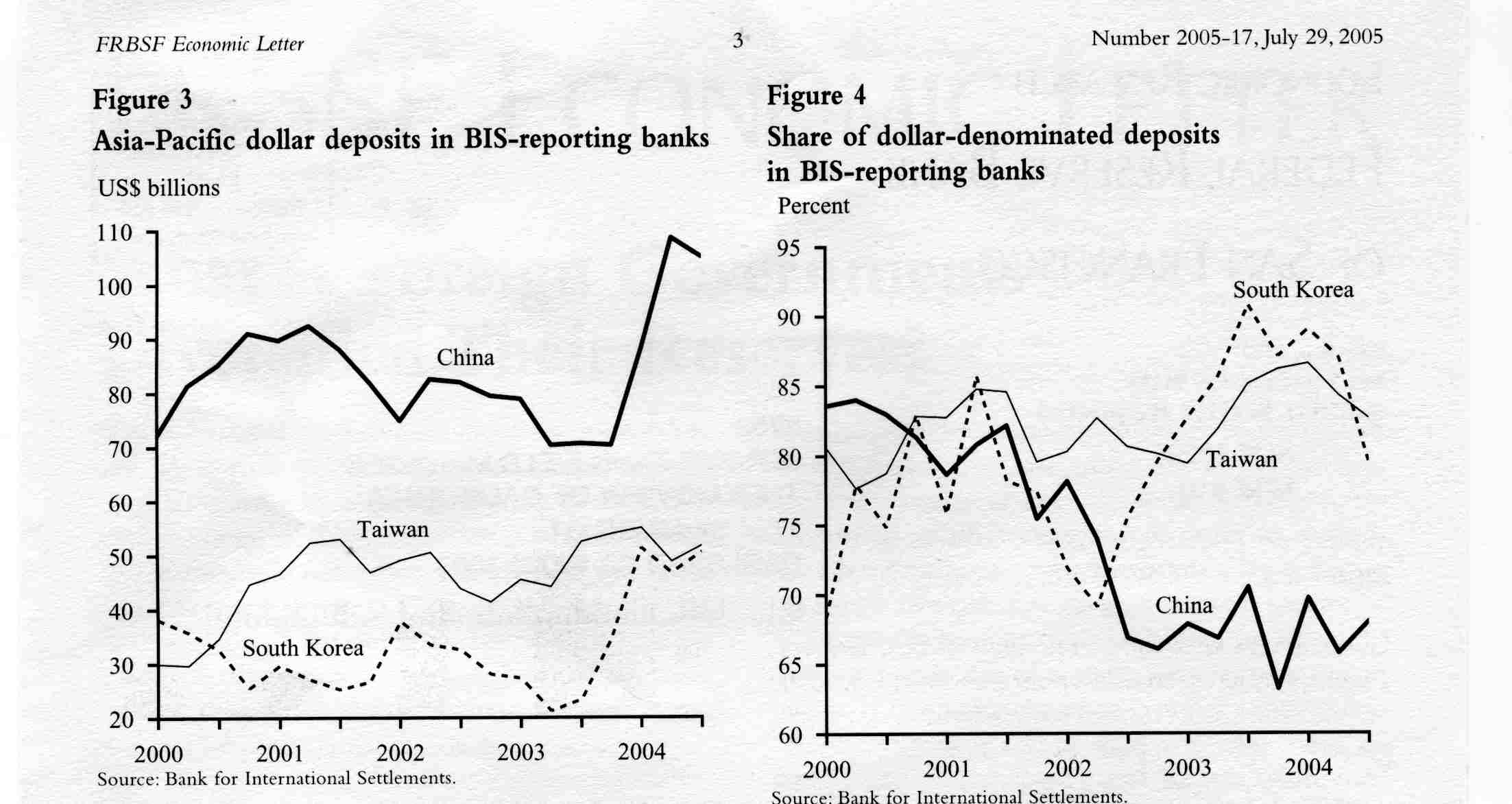

currency crises (Figure 1). At the end of 2004, South Korea held over $200 billion in reserves, more than twice the level

it held in 2000. Figure

1

Official

reserve holdings Total worldwide foreign reserves holdings reached $3 trillion at the end of 2004, up from $2.4 trillion

in 2003, with the largest holders being Japan, at $834 billion, and China, at $615 billion. Most foreign exchange reserves

are held in the form of dollar-denominated securities; one reason for this is that foreign governments like the highly liquid

market for U.S. Treasury securities. As of December 2003, dollar-denominated securities accounted for roughly 70% of total

reserves, while euro-denominated reserves accounted for about 20% (BIS 2004). At the end of 2004, foreign governments

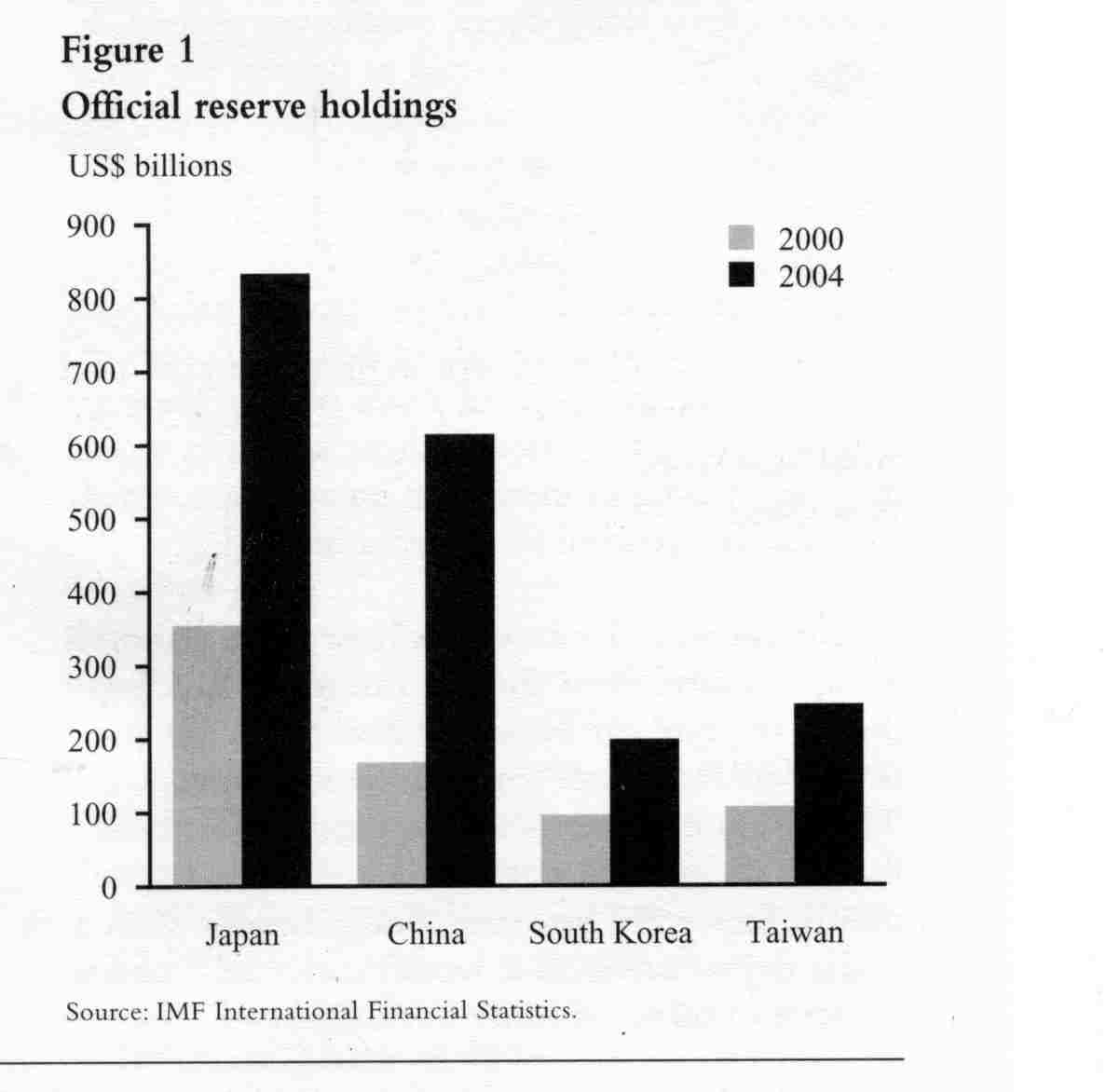

held $1.2 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities, almost double the $609 billion held in 2000. Governments keep the composition of their reserves a well-guarded secret. Therefore, there are no data

on the amount of dollars that individual foreign governments hold in their reserves. However, the U.S. Treasury does have

estimates of total holdings—that is, official plus private—by country. According to those estimates, at the end

of 2004, Japan held $712 billion, China $193 billion, and South Korea $69 billion (Figure 2). Most of these securities are

believed to be held by the central bank of each country. Effects of a sale of dollar-denominated reserves on the U.S. economy The sale of dollar-denominated reserves could have negative effects along several dimensions of the U.S.

economy. First, it would tend to depress the value of the dollar vis-a-vis other currencies. A depreciation of the dollar

in turn would tend to raise import prices, which could feed through to higher consumer price inflation. Since 2002, the dollar

has depreciated by 25.7%, and import prices have increased by 6.6%. If the sale of dollar-denominated reserves took the form

of a sale of U.S. Treasury securities, then the price of these securities would decrease, causing an increase in interest

rates, which may also be harmful to the economy. Furthermore, U.S. consumers have benefited from cheap imports from abroad, and many U.S. producers

depend on imported raw materials and intermediate inputs for their production plans. Thus, both consumers and producers would

be hurt by an increase in the price of intermediate inputs. Exporters, however, would benefit from a dollar depreciation,

as it would make their goods cheaper in terms of other currencies. A depreciation

of the dollar would eventually lead to an improvement in the current account deficit—which reached a record 6.3% of

GDP in the fourth quarter of 2004—through its negative impact on imports and positive impact on exports.

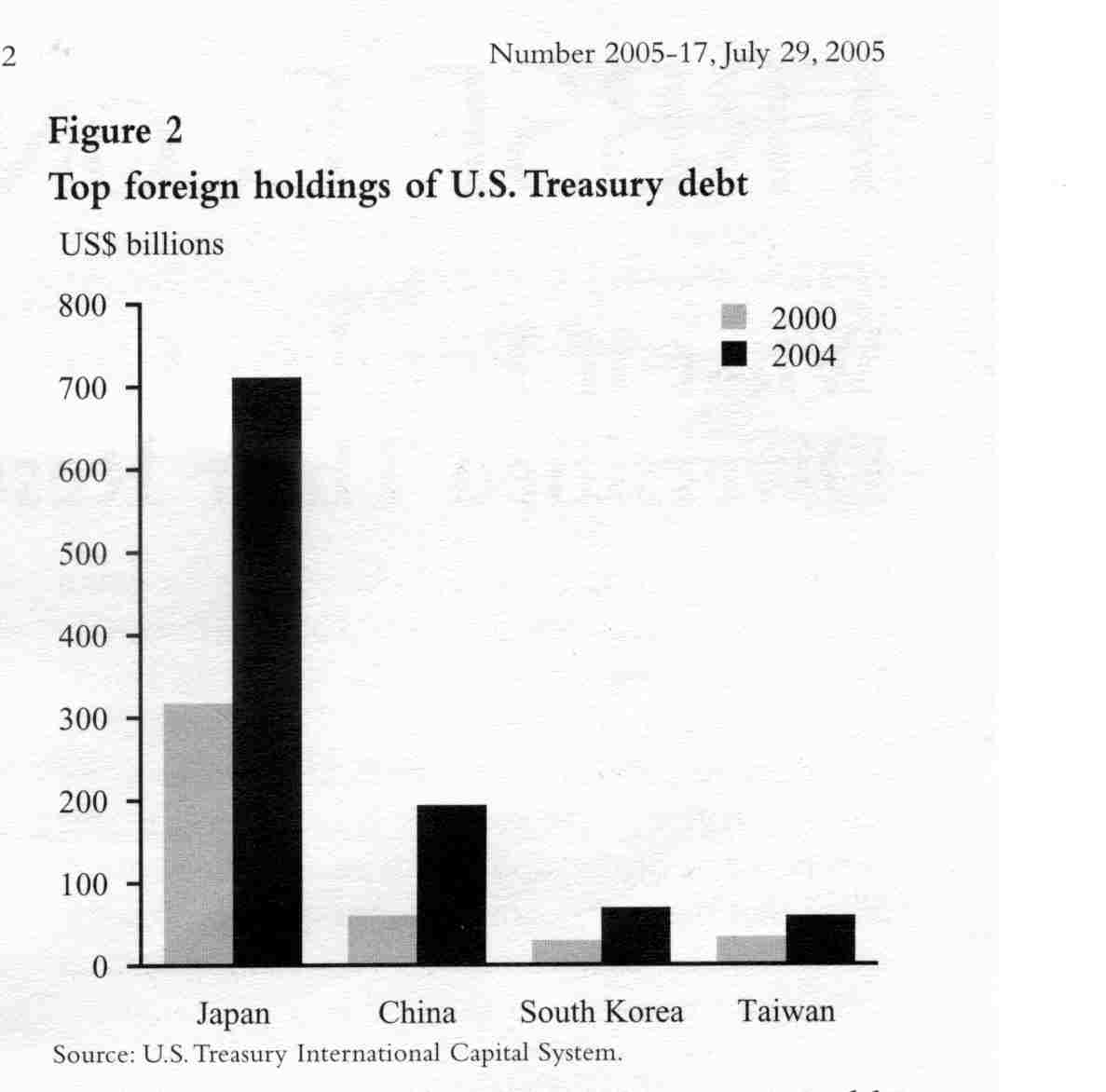

Figure

3 Asia-Pacific

dollar deposits in BIS-reporting banks Larger amounts of securities denominated in other currencies in the future instead of by selling current

holdings of dollar-denominated assets. For example, it is possible that the euro will grow in importance as an international

reserve currency as the European Central Bank cements its low-inflation performance and as the euro financial market develops. A sale of dollar-denominated reserves may be costly to foreign economies In many Asian countries, economic growth has been led by the export sector, which would be hurt by an appreciation

of the local currency vis-a-vis the dollar. In fact, the economies of Japan and South Korea would grow more slowly were it

not for their dynamic export sectors. Thus, a significant move away from dollar-denominated reserves would entail significant

costs to foreign economies. A sale of dollar-denominated assets that leads to a large depreciation of the dollar would generate large

capital losses for foreign governments, as the value of their assets would drop with respect to their domestic currency. On

the other hand, since the United States borrows internationally mostly in terms of dollars and since most of its foreign assets

are denominated in foreign currencies, it would receive most of the capital gains, as the value of its liabilities would drop

relative to the value of its assets. Tille (2005) estimates that a 10% depreciation of the dollar leads to a valuation loss

for foreign economies equivalent to about 4% of U.S. GDP. Conclusions This Economic Letter posed the question: What if foreign central banks diversified their reserves?

The Figure

4 answer

has several dimensions. A sale of dollar-denominated reserves would depress the value of the dollar vis-a-vis other currencies,

thus raising import prices for U.S. consumers and feeding into higher consumer price inflation. If the depreciation is sudden

and leads to a rapid reversal of the current account, it may depress investment and consumption. However, a sale of dollar-denominated

securities would also be costly to foreign economies. Foreign governments would be exposed to large capital losses, and an

appreciation of their currencies would make their exports less competitive. Finally, the case of China makes it clear that

if foreign governments want to diversify their holdings of reserves, they can do so not only by selling dollar-denominated

securities but also by buying into securities denominated in other currencies.

Diego

Valderrama Economist References [URLs accessed July 2005.] Bank for International Settlements. 2004. Annual Report. http://www.bis.org/publ/ar2004e.htni

Bank for International Settlements. 2005. BIS Quarterly RaAeiv

(March). http://www.bis.org/publ/r_qt0503.htm Dougherty, Carter. 2005. "Dollar Plunges on Proposal by Korea Bank to Diversify." Neu'York Times (February

23, 2005) sec. C, p. 12, col. 5, national edition. Koizumi, Junichiro. 2005. Remarks before Japanese Parliament, March 10, 2005. Setser, Brad, and Nouriel Roubini. 2005. "How Scary

Is the Deficit?" Foreign Affairs. (July/August) pp. 194-200. Tille, Cedric.

2005. "Financial Integration and the Wealth Effect of Exchange

Rate Fluctuations." Mimeo. FRB New York. Bush’s Big Give Away On June 7 President George W. Bush celebrated his first

big legislative victory. Only two weeks earlier his new administration had suffered a terrible political blow, when a Republican

senator left the party and gave Democrats a one-vote majority in the Senate. But the administration was nevertheless able

to persuade a dozen Democratic senators to vote its way and authorize a tax cut that would decrease federal tax revenues by

some $1.35 trillion between then and 2010. This was presented at the time

as a way to avoid the "problem" of paying down the federal debt too fast. According to the administration's forecasts, the government was on the way to running up $5.6 trillion (independent forecasts are $7 trillion, and there is interest payment on top of that—jk) in surpluses over the

coming decade. The entire federal debt accumulated between the nation's founding and 2001 totaled only about $3.2 trillion—and

for technical reasons at most $2 trillion of that total could be paid off within the next decade. 4 Therefore some

$3.6 trillion in "unusable" surplus—or about $12,000 for every American—was likely to pile up in the Treasury.

The administration proposed to give slightly less than half of that back through tax cuts, saving the rest for Social Security

and other obligations. A year later the budget would show a deficit of $158 billion; a year after that $378 billion. By the

end of Bush's second term the federal debt, rather than having nearly disappeared, as he expected, had tripled. Through four decades and through administrations as diverse as Lyndon Johnson's and Ronald Reagan's, federal

tax revenue had stayed within a fairly narrow band. The tax cuts of 2001 pushed it out of that safety zone, reducing it to

its lowest level as a share of the economy in the modern era. Late in 2003 Congress

dramatically escalated the fiscal problem by adding prescription-drug coverage to Medicare, with barely any discussion of

its long-term cost. David M. Walker, the government's comptroller general at the time, said that the action was part of "the

most reckless fiscal year in the history of the Republic," because that vote and a few other changes added roughly $13 trillion

to the government's long-term commitments. For the

best account of the Federal Reserve (http://www.freedocumentaries.org/film.php?id=214). One cannot understand |