DURING the cold war, as the Soviet economic system slowly unraveled, internal

reform was impossible because highly placed officials who recognized the systemic disorders could not talk about them honestly.

The United States is now in an equivalent predicament. Its weakening position in the global trading system is obvious and

ominous, yet leaders in politics, business, finance and the news media are not willing to discuss candidly what is happening

and why. Instead, they recycle the usual bromides about the benefits of free trade and assurances that everything will work

out for the best.

Much like Soviet leaders, the American establishment is enthralled by

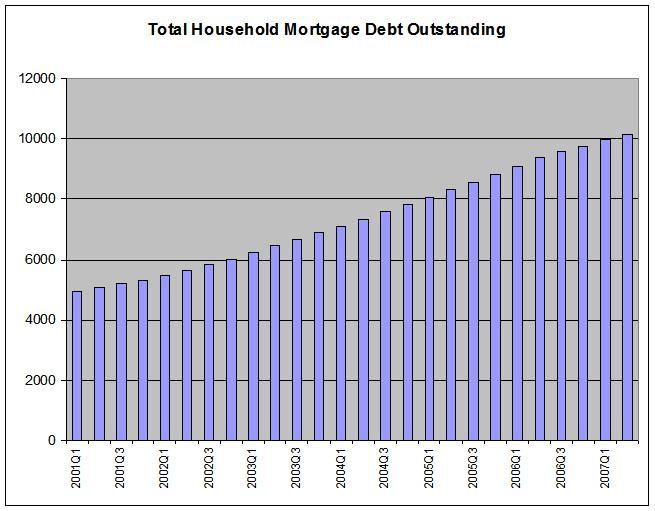

utopian convictions - the market orthodoxy of free trade globalization. The United States is heading for yet another record

trade deficit in 2005, possibly 25 percent larger than last year's. Our economy's international debt position - accumulated

from many years of tolerating larger and larger trade deficits - began compounding ferociously in the last five years. Our

net foreign indebtedness is now more than 25 percent of gross domestic product and at the current pace will reach 50 percent

in four or five years .

For years, elite opinion dismissed the buildup of foreign indebtedness

as a trivial issue. Now that it is too large to deny, they concede the trend is "unsustainable." That's an economist's euphemism

which means: things cannot go on like this, not without ugly consequences for American living standards. But why alarm the

public? The authorities assure us timely policy adjustments will fix the matter. Reporters

and editors typically take cues from the same influential sources and learned experts in business, finance and government.

If the news media decided to cast these facts as the story of the world's only superpower losing ground in global competition

and becoming financially dependent on strategic rivals like China, the public would take greater notice. But governing elites

would regard such clarity as inflammatory. America's awesome trade problem is instead portrayed as something else - an esoteric

technical dispute about currency values, the dollar versus the Chinese yuan. The context is guaranteed to baffle and benumb

citizens.

The possibility that the United States can no longer afford globalization,

at least not as it now functions, is what opinion leaders do not wish to discuss. A few brave dissenters have stated the matter

plainly and called for significant policy shifts to stop the hemorrhaging. Warren Buffett, the legendary investor, says the

United States is destined to become not an "ownership society," but a "sharecropper society." But his analysis, and others

like it, are brushed aside.

An authentic debate might start by asking heretical questions: Why is the United

States one of the few advanced economies that suffers from perennial trade deficits? Why do new trade agreements, despite

official promises, always leave the United States with a deeper deficit hole, with another wave of jobs moving overseas? How

do the authorities explain the 30-year stagnation of working-class wages that is peculiar to America? Are we supposed to believe

that everyone else is simply more competitive or slyly breaking the rules? In the last three decades, American policymakers

have succeeded in closing the trade gap with only one event - a recession.

The American predicament is shaped by operating dynamics grounded in the

global system, singularly embraced by Washington because Washington originated most of them. At the outset, these practices

were both virtuous and self-interested for the United States - encouraging industrialization in poor countries, binding cold

war allies together with trade and investment, furthering the global advance of American business and finance. With its wide-open

market, America played - and still plays - buyer of last resort for world exports. Its leading companies and banks gained

access to developing new markets, often by sharing jobs, production and technology with others. American policymakers also

got to run the world.

The utopian expectations behind this arrangement turned out to be wrong,

judging by empirical evidence rather than theory. But why wrong? American political debate is enveloped by the ideology of

free trade, but "free trade" does not actually describe the global economic system. A more accurate description would be "managed

trade" - a dense web of bargaining and deal-making among governments and multinational corporations, all with self-interested

objectives that the marketplace doesn't determine or deliver. Every sovereign nation, the United States included, uses its

vast arsenal of policies to pursue its national interest. But on the crucial

question of how policy makers define "national interest," Washington stands alone. Western Europe, whatever its problems,

manages economic policy to maintain modest trade surpluses. Japan manages to insure far larger surpluses in recessions (its

export income subsidizes inefficient domestic employers). China strives to acquire a larger, more advanced industrial base

at the expense of worker incomes and bank profits. Germany and Japan, despite vast differences,

both manage to keep advanced manufacturing sectors anchored at home and to defend domestic wage levels and social guarantees.

When they do disperse production and jobs overseas,

as they must, they do so strategically. By

contrast, Washington defines "national interest" primarily in terms of advancing the global reach of our multinational enterprises.

Elites are persuaded by the reigning orthodoxy that subsidiary domestic interests will ultimately

benefit too. The distinctive power of America's globalized companies is reflected in trade patterns. Nearly half of American

exports and imports are not traded in open markets - the price auction idealized by neoclassical economics - but within the

companies themselves, moving materials and components back and forth among their far-flung factories. A trade deficit does

not show on the company's balance sheet, only on the nation's. In recent years,

much of the trade deficit has reflected the value-added production and jobs that companies moved elsewhere.

The United States is thus especially vulnerable to the downward pressures

on working-class wages that exist on both ends of the global system. American producers are generally free - and even encouraged by Washington - to shift

production to low-wage locations. Companies regularly use this cost-cutting technique as a competitive weapon without regard

to the domestic consequences. The practice works for companies and investors, but not so well for a nation. INDEED, the cumulative effects of retarding labor incomes worldwide repeatedly threatens stagnation or worse

for the entire system. Workers, to put it crudely, cannot buy what the world can make. Too much capital leads to the speculative

"bubbles" that bounce around the world, visiting financial crisis on rich and poor alike.

At a different moment in history, American leadership might have stepped

up to these disorders and led the way to solutions. If globalization is to continue without encountering more crisis and random

destruction, governments must together shift the balance of power so labor incomes can rise in step with rising productivity

and profits. If the United States is to avert its own reckoning, it must take decisive action to draw firm limits on its exposure

to trade deficits, that is, resign its position as the open-armed buyer of last resort. In effect, Washington would also reform

its own national interest imperatives so that they more closely resemble what other nations already embrace. Ultimately, American

remedial action may protect the global system from its own crisis - the moment when trading partners discover they have just

lost their best customer. But to describe plausible remedies is to explain why

none are likely. The webs of mutual interests connecting government, corporate boardrooms

and Wall Street are too deeply woven, as are habits of thought among policy makers and politicians.

So I do not expect anything fundamental will be altered in time. We are going to find out if the dissenters are right.

William Greider, the national affairs columnist of The Nation, is the author

of "One World, Ready or Not."