|

Discovery of the Psychic Effects of LSD

The solution of the ergotoxin problem had led to fruitful results, described here

only briefly, and had opened up further avenues of research. And yet I could not forget

the relatively uninteresting LSD-25. A peculiar presentiment—the feeling that this substance could possess properties other than those established in the first investigations—induced

me, five years after the first synthesis, to produce LSD-25 once again so that

a sample could be given to the pharmacological department for further tests.

This was quite unusual; experimental substances, as a rule, were definitely stricken from the research program if once found to be lacking in pharmacological interest.

Nevertheless,

in the spring of 1943, I repeated the synthesis of LSD-25. As in the first synthesis,

this involved the production of only a few centigrams of the compound.

In the

final step of the synthesis, during the purification and crystallization of lysergic acid

diethylamide in the form of a tartrate (tartaric acid salt), I was interrupted in my work by unusual

sensations. The following description of this incident comes from the report that I sent at the time to Professor Stoll:

Last Friday, April 16, 1943,1 was forced to interrupt my work in the laboratory in the

middle

of the afternoon and proceed home, being affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined

with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated like condition, characterized by an extremely

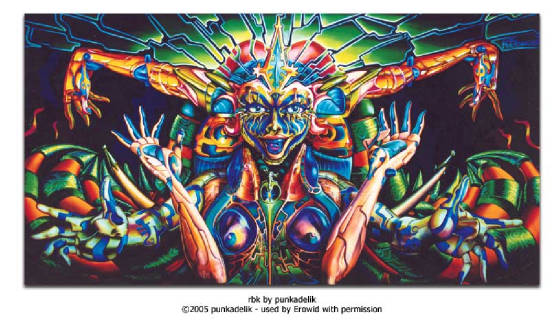

stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived

an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense,

kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away.

This was, altogether,

a remarkable experience— both in its sudden onset and its extraordinary course.

It seemed to have resulted from some external toxic influence; I surmised a connection

with the substance I had been working with at the time, lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate. But this led to another question: how had I managed to absorb this material? Because of the known

toxicity of ergot substances, I always maintained meticulously neat work habits. Possibly

a bit of the LSD solution had contacted my fingertips during crystallization,

and a trace of the substance was absorbed through the skin. If LSD-25 had indeed been the cause of this bizarre experience, then it must be a substance of

extraordinary potency. There seemed to be only one way of getting to the bottom of this. I decided on a self-experiment.

Exercising extreme

caution, I began the planned series of experiments with the smallest quantity that could be expected to produce some effect, considering the activity of the ergot alkaloids known at the time: namely, 0.25 mg

(mg = milligram = one thousandth of a gram) of lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate. Quoted below is the entry for this experiment in my laboratory journal of April

19, 1943. The first section contains notes on the production of the tartrate (tartaric

acid salt) of LSD.

Self-Experiments

4/19/43 16:20: 0.5 cc of Vi promil aqueous solution of diethylamide tartrate orally = 0.25 mg tartrate. Taken diluted with about 10 cc water. Tasteless.

17:00: Beginning dizziness, feeling of anxiety, visual distortions, symptoms of

paralysis, desire to laugh.

Supplement of 4/21: Home by bicycle. From 18:00-ca. 20:00 most severe crisis. (See special

report.)

Here the notes in my laboratory journal cease. I was able to write the last words

only with great effort. By now it was already clear to me that LSD had been the cause of the remarkable experience of the previous Friday, for the altered perceptions were of the same

type as before, only much more intense. I had to struggle to speak intelligibly. I asked my laboratory assistant, who was informed

of the self-experiment, to escort me home. We went by bicycle, no automobile being

available because of wartime restrictions on their use. On the way home, my condition

began to assume threatening forms. Everything in my field of vision wavered and

was distorted as if seen in a curved mirror. I also had the sensation of being

unable to move from the spot. Nevertheless, my assistant later told me that we had traveled very rapidly. Finally, we arrived at home

safe and sound, and I was just barely capable of asking my companion to summon

our family doctor and request milk from the neighbors.

In spite of my delirious, bewildered condition, I had brief periods of clear and effective

thinking—and chose milk as a nonspecific antidote for poisoning.

The dizziness and sensation of fainting became so strong at times that I could no

longer hold myself erect, and had to lie down on a sofa. My surroundings had now transformed

themselves in more terrifying ways. Everything in the room spun around, and the familiar

objects and pieces of furniture assumed grotesque, threatening forms. They were in continuous motion, animated, as if

driven by an inner restlessness. The lady next door, whom I scarcely recognized, brought me milk—in the course of the evening I drank more than two liters. She

was no longer Mrs. R., but rather a malevolent, insidious witch with a colored mask.

Even worse than these demonic transformations of the outer world, were the alterations that I perceived in myself, in my inner being. Every exertion of my will, every attempt

to put an end to the disintegration of the outer world and the dissolution of

my ego, seemed to be wasted effort. A demon had invaded me, had taken possession of my body, mind, and soul. I jumped up and

screamed, trying to free myself from him, but then sank down again and lay helpless on the sofa.

The substance, with which I had wanted to experiment, had vanquished me. It was the demon that scornfully

triumphed over my will. I was seized by the dreadful fear of going insane.

I was taken to another world, another place, another time. My body seemed to be without

sensation, lifeless, strange. Was I dying? Was this the transition? At times I believed myself

to be outside my body, and then perceived clearly, as an outside observer, the

complete tragedy of my situation. I had not even taken leave of my family (my wife,

with our three children had traveled that day to visit her parents, in Lucerne).

Would they ever understand that I had not experimented thoughtlessly, irresponsibly, but rather with the utmost caution, and that such a result was in no way foreseeable?

My fear and despair intensified, not only because a young family should

lose its father, but also because I dreaded leaving my chemistry research work, which meant

so much to me, unfinished in the midst of fruitful, promising development.

Another reflection took shape, an idea full of bitter irony: if I was now forced to leave this

world prematurely, it was because of this lysergic acid diethylamide that I myself

had brought forth into the world.

By the time the doctor arrived, the climax of my despondent condition had

already passed. My

laboratory assistant informed him about my self-experiment, as I myself was not yet able to formulate

a coherent sentence. He shook his head in perplexity, after my attempts to describe the mortal danger that threatened my body.

He could detect no abnormal symptoms other than extremely dilated pupils. Pulse,

blood pressure, breathing were all normal. He saw no reason to prescribe any medication.

Instead he conveyed me to my bed and stood watch over me. Slowly I came back from a weird, unfamiliar world to reassuring everyday reality. The horror softened and gave way to a feeling of good fortune and gratitude, the more

normal perceptions and thoughts returned, and I became more confident that the danger

of insanity was conclusively past.

Now, little by little I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colors and plays

of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes. Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images surged

in on me, alternating, variegated, opening and then closing themselves in circles and

spirals, exploding in colored fountains, rearranging and hybridizing themselves

in constant flux. It was particularly remarkable how every acoustic perception,

such as the sound of a doorhandle or a passing automobile, became transformed into

optical perceptions. Every sound generated a vividly changing image, with its own consistent form and color.

Late in the evening my wife returned from Lucerne. Someone had informed her by telephone

that I was suffering a mysterious breakdown. She had returned home at

once, leaving the children behind with her parents. By now, I had recovered myself sufficiently

to tell her what had happened.

Exhausted,

I then slept, to awake next morning refreshed, with a clear head, though still somewhat tired physically. A sensation

of well-being and renewed life flowed through me. Breakfast tasted delicious and gave me extraordinary pleasure. When I later walked out

into the garden, in which the sun shone now after a spring rain, everything glistened

and sparkled in a fresh light. The world was as if newly created. All my senses vibrated in a condition of highest sensitivity, which persisted for the entire day.

This self-experiment

showed that LSD-25 behaved as a psychoactive substance with extraordinary properties and potency.

There was to my knowledge no other known substance that evoked such profound psychic

effects in such extremely low doses that caused such dramatic changes in human consciousness and our experience of the inner and outer world.

What seemed

even more significant was that I could remember the experience of LSD inebriation in every detail. This could only mean that the conscious recording function was not interrupted,

even in the climax of the LSD experience, despite the profound breakdown of the normal

worldview. For the entire duration of the experiment, I had even been aware of participating in an experiment, but despite this recognition of my condition, I could not, with every exertion

of my will, shake off the LSD world. Everything was experienced as completely real, as alarming

reality; alarming, because the picture of the other, familiar everyday reality was still fully preserved in the memory for comparison.

Another surprising aspect of LSD was its ability to

produce such a far-reaching,

powerful state of inebriation without leaving a hangover. Quite the contrary,

on the day after the LSD experiment I felt myself to be as already described, in excellent

physical and mental condition.

I was aware that LSD, a new active compound with such properties, would have to be of use in

pharmacology, in neurology, and especially in psychiatry, and that it

would attract the interest of concerned specialists. But at that time I had no inkling that

the new substance would also come to be used beyond medical science, as an intoxicant in the drug scene.

Since my self-experiment had revealed LSD in its terrifying, demonic aspect,

the last thing I could have expected was that this substance could ever find application as anything approaching a pleasure

drug. I failed, moreover, to recognize the meaningful connection between LSD inebriation and spontaneous visionary experience until much later, after further experiments, which were carried out with far lower doses and under different conditions.

Next day I wrote to Professor Stoll the above-mentioned report about my extraordinary experience

with LSD-25 and sent a copy to the director of the pharmacological department, Professor Rothlin.

As expected, the first reaction was incredulous astonishment. Instantly a telephone

call came from the management; Professor Stoll asked: "Are you certain you made no mistake in the weighing?

Is the stated dose really correct?" Professor Rothlin also called, asking the same question. I was certain of this point, for I had executed

the weighing and dosage with my own hands. Yet their doubts were justified to

some extent, for until then no known substance had displayed even the slightest

psychic" effect in fraction-of-a-milligram Hoses. An active compound of such potency

seemed almost unbelievable.

Professor Rothlin himself and two of his colleagues were the first to repeat my experiment,

with only one-third of the dose I had utilized. But even at that level, the effects

were still extremely impressive, and quite fantastic. All doubts about the statements in my report

were eliminated.

Note: LSD, My Problem

Child appears in this library under the "Fair Use" rulings

regarding the 1976 Copyright Act for NON-profit academic,

research, and

general information purposes. Readers requiring a permanent copy of

LSD, My Problem Child for their

library are advised to

purchase it from their book supplier

Hofmann’s

own words:

The entire work is on line

at http://www.psychedelic-library.org/child.htm

Albert Hormann, LSD, My Problem Child (the European earlier addition was titled LSD, My Problem Solving

Child—Mein Sorgenkind), translated by Jonathan Ott, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1980, pp 14-21.

By Albert Hofmann

A Short Autobiography

About me:

Albert Hofmann was born

in Baden, Switzerland in 1906.

He graduated from the University of Zürich with a degree in chemistry in 1929 and went to work for Sandoz Pharmaceutical in Basel, Switzerland. With

the laboratory goal of working towards isolation of the active principles of known medicinal plants, Hofmann worked with Mediterranean

squill (Scilla maritima) for several years, before moving on to the study of Claviceps purpurea (ergot) and ergot alkaloids.

Over the next few years, he worked his way through the lysergic acid derivatives, eventually synthesizing LSD-25 for the first

time in 1938. After minimal testing, LSD-25 was set aside as he continued with other derivatives. Four years later, on April 16, 1943, he re-synthesized LSD-25 because he felt he might have missed something the first time around. That day, he

became the first human to experience the effects of LSD after accidentally ingesting a minute amount. Three days later, on

April 19, 1943, he decided to verify his results by intentionally ingesting 250 ug of LSD. This day has become known

as "Bicycle Day" as Hofmann experienced an incredible bicycle ride on his way home from the lab. In addition to his discovery

of LSD, he was also the first to synthesize psilocybin (the active constituent of 'magic mushrooms') in 1958. Albert Hofmann,

known as the 'father of LSD', continued to work at Sandoz until 1971 when he retired as Director of Research for the Department

of Natural Products. Since that time he has continued to write, lecture, and play a leading role as an elder in the psychedelic

community. 8% of the population has tried LSD at least once and it has had a significantly positive impact on millions of

lives. Discovery of the Psychic Effects of LSD. The solution of the ergotoxine

problem had led to fruitful results, described here only briefly, and had opened up further avenues of research. And yet I

could not forget the relatively uninteresting LSD-25. A peculiar presentiment—the feeling that this substance could

possess properties other than those established in the first investigations—induced me, five years after the first synthesis,

to produce LSD-25 once again so that a sample could be given to the pharmacological department for further tests. This was

quite unusual; experimental substances, as a rule, were definitely stricken from the research program if once found to be

lacking in pharmacological interest. Nevertheless, in the spring of 1943, I repeated the synthesis of LSD-25. As in the first

synthesis, this involved the production of only a few centigrams of the compound. In the final step of the synthesis, during

the purification and crystallization of lysergic acid diethylamide in the form of a tartrate (tartaric acid salt), I was interrupted

in my work by unusual sensations. The following description of this incident comes from the report that I sent at the time

to Professor Stoll: Last Friday, April

16,1943, I was forced to interrupt my work in the laboratory

in the middle of the afternoon and proceed home, being affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness.

At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination.

In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream

of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition

faded away. This was, altogether, a remarkable experience—both in its sudden onset and its extraordinary course. It

seemed to have resulted from some external toxic influence; I surmised a connection with the substance I had been working

with at the time, lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate. But this led to another question: how had I managed to absorb this

material? Because of the known toxicity of ergot substances, I always maintained meticulously neat work habits. Possibly a

bit of the LSD solution had contacted my fingertips during crystallization, and a trace of the substance was absorbed through

the skin. If LSD-25 had indeed been the cause of this bizarre experience, then it must be a substance of extraordinary potency.

There seemed to be only one way of getting to the bottom of this. I decided on a self-experiment. Exercising extreme caution,

I began the planned series of experiments with the smallest quantity that could be expected to produce some effect, considering

the activity of the ergot alkaloids known at the time: namely, 0.25 mg (mg = milligram = one thousandth of a gram) of lysergic

acid diethylamide tartrate. Quoted below is the entry for this experiment in my laboratory journal of April 19, 1943. Self-Experiments 4/19/43 16:20: 0.5 cc of 1/2 promil aqueous solution of diethylamide tartrate orally = 0.25 mg tartrate. Taken

diluted with about 10 cc water. Tasteless. 17:00: Beginning dizziness, feeling of anxiety, visual distortions, symptoms of paralysis, desire to laugh.

Supplement of 4/21: Home by bicycle. From 18:00- ca.20:00 most severe crisis. (See special report.) Here the notes in my laboratory

journal cease. I was able to write the last words only with great effort. By now it was already clear to me that LSD had been

the cause of the remarkable experience of the previous Friday, for the altered perceptions were of the same type as before,

only much more intense. I had to struggle to speak intelligibly. I asked my laboratory assistant, who was informed of the

self-experiment, to escort me home. We went by bicycle, no automobile being available because of wartime restrictions on their

use. On the way home, my condition began to assume threatening forms. Everything in my field of vision wavered and was distorted

as if seen in a curved mirror. I also had the sensation of being unable to move from the spot. Nevertheless, my assistant

later told me that we had traveled very rapidly. Finally, we arrived at home safe and sound, and I was just barely capable

of asking my companion to summon our family doctor and request milk from the neighbors. In spite of my delirious, bewildered

condition, I had brief periods of clear and effective thinking—and chose milk as a nonspecific antidote for poisoning.

The dizziness and sensation of fainting became so strong at times that I could no longer hold myself erect, and had to lie

down on a sofa. My surroundings had now transformed themselves in more terrifying ways. Everything in the room spun around,

and the familiar objects and pieces of furniture assumed grotesque, threatening forms. They were in continuous motion, animated,

as if driven by an inner restlessness. The lady next door, whom I scarcely recognized, brought me milk—in the course

of the evening I drank more than two liters. She was no longer Mrs. R., but rather a malevolent, insidious witch with a colored

mask. Even worse than these demonic transformations of the outer world, were the alterations that I perceived in myself, in

my inner being. Every exertion of my will, every attempt to put an end to the disintegration of the outer world and the dissolution

of my ego, seemed to be wasted effort. A demon had invaded me, had taken possession of my body, mind, and soul. I jumped up

and screamed, trying to free myself from him, but then sank down again and lay helpless on the sofa. The substance, with which

I had wanted to experiment, had vanquished me. It was the demon that scornfully triumphed over my will. I was seized by the

dreadful fear of going insane. I was taken to another world, another place, another time. My body seemed to be without sensation,

lifeless, strange. Was I dying? Was this the transition? At times I believed myself to be outside my body, and then perceived

clearly, as an outside observer, the complete tragedy of my situation. I had not even taken leave of my family (my wife, with

our three children had traveled that day to visit her parents, in Lucerne). Would they ever understand

that I had not experimented thoughtlessly, irresponsibly, but rather with the utmost caution, an-d that such a result was

in no way foreseeable? My fear and despair intensified, not only because a young family should lose its father, but also because

I dreaded leaving my chemical research work, which meant so much to me, unfinished in the midst of fruitful, promising development.

Another reflection took shape, an idea full of bitter irony: if I was now forced to leave this world prematurely, it was because

of this Iysergic acid diethylamide that I myself had brought forth into the world. By the time the doctor arrived, the climax

of my despondent condition had already passed. My laboratory assistant informed him about my self-experiment, as I myself

was not yet able to formulate a coherent sentence. He shook his head in perplexity, after my attempts to describe the mortal

danger that threatened my body. He could detect no abnormal symptoms other than extremely dilated pupils. Pulse, blood pressure,

breathing were all normal. He saw no reason to prescribe any medication. Instead he conveyed me to my bed and stood watch

over me. Slowly I came back from a weird, unfamiliar world to reassuring everyday reality. The horror softened and gave way

to a feeling of good fortune and gratitude, the more normal perceptions and thoughts returned, and I became more confident

that the danger of insanity was conclusively past. Now, little by little I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colors and

plays of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes. Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images surged in on me, alternating, variegated,

opening and then closing themselves in circles and spirals, exploding in colored fountains, rearranging and hybridizing themselves

in constant flux. It was particularly remarkable how every acoustic perception, such as the sound of a door handle or a passing

automobile, became transformed into optical perceptions. Every sound generated a vividly changing image, with its own consistent

form and color. Late in the evening my wife returned from Lucerne. Someone had informed her by telephone that I was suffering a mysterious breakdown. She had returned home

at once, leaving the children behind with her parents. By now, I had recovered myself sufficiently to tell her what had happened.

Exhausted, I then slept, to awake next morning refreshed, with a clear head, though still somewhat tired physically. A sensation

of well-being and renewed life flowed through me. Breakfast tasted delicious and gave me extraordinary pleasure. When I later

walked out into the garden, in which the sun shone now after a spring rain, everything glistened and sparkled in a fresh light.

The world was as if newly created. All my senses vibrated in a condition of highest sensitivity, which persisted for the entire

day. This self-experiment showed that LSD-25 behaved as a psychoactive substance with extraordinary properties and potency.

There was to my knowledge no other known substance that evoked such profound psychic effects in such extremely low doses,

that caused such dramatic changes in human consciousness and our experience of the inner and outer world. What seemed even

more significant was that I could remember the experience of LSD inebriation in every detail. This could only mean that the

conscious recording function was not interrupted, even in the climax of the LSD experience, despite the profound breakdown

of the normal world view. For the entire duration of the experiment, I had even been aware of participating in an experiment,

but despite this recognition of my condition, I could not, with every exertion of my will, shake off the LSD world. Everything

was experienced as completely real, as alarming reality; alarming, because the picture of the other, familiar everyday reality

was still fully preserved in the memory for comparison. Another surprising aspect of LSD was its ability to produce such a

far-reaching, powerful state of inebriation without leaving a hangover. Quite the contrary, on the day after the LSD experiment

I felt myself to be, as already described, in excellent physical and mental condition. I was aware that LSD, a new active

compound with such properties, would have to be of use in pharmacology, in neurology, and especially in psychiatry, and that

it would attract the interest of concerned specialists. But at that time I had no inkling that the new substance would also

come to be used beyond medical science, as an inebriant in the drug scene. Since my self-experiment had revealed LSD in its

terrifying, demonic aspect, the last thing I could have expected was that this substance could ever find application as anything

approaching a pleasure drug. I failed, moreover, to recognize the meaningful connection between LSD inebriation and spontaneous

visionary experience until much later, after further experiments, which were carried out with far lower doses and under different

conditions. The next day I wrote to Professor Stoll the above-mentioned report about my extraordinary experience with LSD-25

and sent a copy to the director of the pharmacological department, Professor Rothlin. As expected, the first reaction was

incredulous astonishment. Instantly a telephone call came from the management; Professor Stoll asked: "Are you certain you

made no mistake in the weighing? Is the stated dose really correct?" Professor Rothlin also called, asking the same question.

I was certain of this point, for I had executed the weighing and dosage with my own hands. Yet their doubts were justified

to some extent, for until then no known substance had displayed even the slightest psychic effect in fraction-of-a-milligram

doses. An active compound of such potency seemed almost unbelievable. Professor Rothlin himself and two of his colleagues

were the first to repeat my experiment, with only one-third of the dose I had utilized. But even at that level, the effects

were still extremely impressive, and quite fantastic. All doubts about the statements in my report were eliminated. http://www.psychedelic-library.org/child.htm

|